Buffy and her friends spend a lot of time reading. This is uncharacteristic enough for a Hollywood prime-time serial drama (it’s practically un-American). But more specifically, they spend a lot of time doing research: finding the most authoritative sources on a subject, reading up, and discussing what they read. And it’s rare that the research doesn’t pay off, in one way or another; most often, it pays off in critical discoveries and insights, knowledge of the situations, events, and adversaries they face, of the histories that have produced them, and sometimes even of vital knowledge of self. That knowledge reliably then helps Buffy to kick serious demonic ass. Buffy the Vampire Slayer routinely dramatizes research in action as a public good.

Buffy and her friends spend a lot of time reading. This is uncharacteristic enough for a Hollywood prime-time serial drama (it’s practically un-American). But more specifically, they spend a lot of time doing research: finding the most authoritative sources on a subject, reading up, and discussing what they read. And it’s rare that the research doesn’t pay off, in one way or another; most often, it pays off in critical discoveries and insights, knowledge of the situations, events, and adversaries they face, of the histories that have produced them, and sometimes even of vital knowledge of self. That knowledge reliably then helps Buffy to kick serious demonic ass. Buffy the Vampire Slayer routinely dramatizes research in action as a public good.

One of the main protagonists, the “watcher” Giles – Buffy’s supervisor and paternal sort of mentor – is a librarian, who runs the high school library. For all the predictable tweedy jokes, the character is an essential part of the team, as readily looked to as leader as the slayer herself. Giles demonstrates research best practices by cultivating an important specialist collection (although its place in a public secondary school is curious, and sometimes challenged by parents and other authority characters), by identifying the best sources on certain subjects, and by putting in the time and effort that research needs to take if it is to prove valuable.

In an early, character-establishing first-season episode, Buffy’s friend Willow asks Giles:

–How is it you always know this stuff? You always know whats going on. I never know whats going on.

–You werent here from midnight till six researching it.

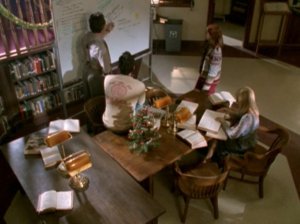

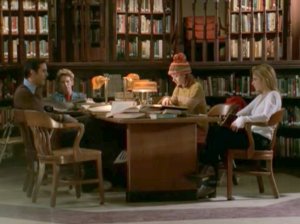

This is a teachable moment: in subsequent episodes, the whole team is often shown in marathon, wee-hours research tableaus and montages. Here are still frames from one such typical montage, in season three’s episode 10 (“Amends”).

For the first three seasons, then, the school library is a regular setting for scenes in the series, scenes of research, and of modeling how to do research. The library setting also thus comments on the anti-intellectual ideology that’s more common and prevalent in popular culture. Except for the main protagonists, the school library is usually deserted. When student character extras enter, the protagonists meet them with surprise and bewilderment. That the library has an extensive specialized collection of rare and ancient texts on withcraft and demonology goes largely unnoticed by other characters, except in one third-season episode (“Gingerbread’) in which Buffy’s mother spearheads a moral panic and literal witch hunt, leading to the police confiscation of Giles’ specialist archive, and culminating in a witch- and book-burning denouement.

The series script regularly has characters recognizing a need for and then conducting research, often in montage scenes to suggest the significant time and effort that goes into the research process. There are plenty of jokes about how research is tiring, isn’t fun, and so on, but the protagonists still commit to it – and it usually brings results. Their research regularly results in knowledge that helps and often saves individuals, groups, the town, the world. The series reinforces its valuation of research too by dramatizing inattention and lack of rigour as research practice errors that make bad situations worse. For instance, in the third-season episode in which an imported face mask begins producing zombies, an early scene shows Giles absentmindedly turning pages in a book, ostensibly researching, but flipping past the page that illustrates and describes the mask. The show makes it imperative not only that one does one’s homework, but that one does it well: using the best sources and reading them diligently.

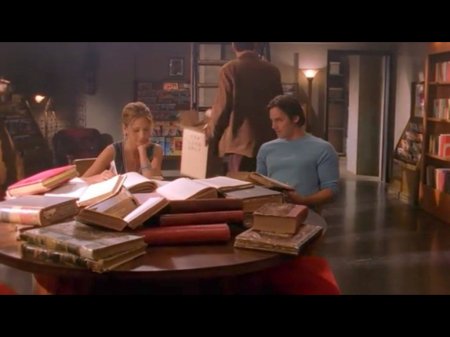

As the series progresses, the fact that Buffy and her team graduate from high school and go to college doesn’t change their need to do research, but changes the dramatic sites in which research is done. Interestingly, in the fourth season, as Buffy and Willow begin college, the first episode briefly shows the college library as a serious research library that dwarfs the school’s; however, the protagonists are never shown doing research there. That they refrain from researching in the university library suggests that library – unlike the school’s – does actually get used by other students, and doesn’t house the specialized archive they need. So instead, the library moves, becomes portable – and, interestingly, more privatized. In the fourth season, most of the research is done at Giles’ own home.

In the fifth season, when he buys the town magic shop, this retail store becomes the repository for Giles’ collection and the primary site in which the team carries out its researches.

The series thus both promotes the value of research as a public good, and – ironically if not downright paradoxically – performs the privatization of research resources, in the migration of the team’s library from the high school, to the librarian’s home, to a retail store. Buffy the Vampire rewards rewatching today with a critical eye to its representations of research, given significant developments in research and its regulation. At the global level, the various policies and trade deals that purport to strengthen copyright law, taken together, represent a multilateral, globalized campaign not only to protect Big Content businesses but even to control the Internet, to regulate and curb its demonstrated potential to subvert modern forms of state governance. At the regional level, the overdeveloped Anglophone world (e.g. the USA, the UK, Canada) privileges private corporate interests whose client governments are carrying out a systematic program of what political science professor Janine Brodie calls “manufactured ignorance”: the active destruction – through “austerity” and other policy measures – of citizens’ “social literacy,” that is, a people’s knowledge of self and history as a people. Canada, for example, has recently witnessed deep budget cuts to libraries, archives, and public broadcasting, as well as the active government muzzling of climate change researchers.  To retrieve, today, a popular cultural product, from the not-so-distant past, that prominently promotes research as the first step of effective social action – a vital contribution to the public good – is a most welcome research result. It’s a lesson in history, as conceptualized by Walter Benjamin: history is the critical image that flashes before you at a moment of danger. And so, I might add, is research.

To retrieve, today, a popular cultural product, from the not-so-distant past, that prominently promotes research as the first step of effective social action – a vital contribution to the public good – is a most welcome research result. It’s a lesson in history, as conceptualized by Walter Benjamin: history is the critical image that flashes before you at a moment of danger. And so, I might add, is research.

Works Cited

Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Writ. Joss Whedon. Warner Bros./Paramount, 1997-2003.

Brodie, Janine. “Manufacturing ignorance: Harper, the census, social inequality.” Canada Watch Spring 2011. 30-31. http://robarts.info.yorku.ca/files/2012/03/CW_Spring2011.pdf

—. “On courage, social justice, and policymaking.” Rabble.ca 16 Sept. 2012. http://rabble.ca/news/2011/09/courage-social-justice-and-policy-making

Screen frames from Buffy the Vampire Slayer used under fair dealing provisions of Canadian copyright law.